Introduction – A Taste of Early Irish Law

Long before the arrival of the Normans or the spread of common law, Ireland was governed by one of the oldest and most sophisticated legal systems in Europe: the Brehon Laws. Rooted in custom and upheld by professional judges known as brehons, this system regulated everything from marriage and land ownership to hospitality and farming. And at the heart of early Irish society—binding families, neighbours, and entire clans together—was food.

Food was more than sustenance; it was a symbol of status, a token of justice, and a legal obligation. The Brehon Laws provided detailed guidance on what people could grow, how they should share it, and even what was owed to a guest or client in terms of hospitality. The laws recognised the land’s bounty as central to life, but also as a resource to be respected and managed fairly.

Farming, Land, and the Law – Cultivating the Early Irish Landscape

In early Ireland, land wasn’t just the backdrop to life—it was life itself. The Brehon Laws placed enormous emphasis on how land was used, shared, and farmed, reflecting a society that depended heavily on the soil for survival. Ownership of land was communal in many cases, with extended families (fine) holding collective rights to farm, graze, and harvest from shared plots.

Farming rights were tightly regulated, and misuse of land was a serious offence. If a person allowed livestock to overgraze another’s field or failed to maintain hedges and boundaries, they could be fined or ordered to provide compensation—in produce, not coin. The law even accounted for different types of soil, recognising the difference between fertile land (tir méith) and rough, less productive ground (tir garbh), ensuring fair expectations and responsibilities for farmers.

Crop rotation, fallow fields, and seasonal sowing were all recognised in the law, not as science, but as custom passed down through generations. There were also rules around communal ploughing, and those who borrowed tools, seeds, or animals had strict obligations to return them in good condition—or offer repayment in grain, milk, or labour.

Through it all, the Brehon Laws maintained a balance: encouraging productivity while protecting the land from exploitation. Farming wasn’t just a job—it was a shared duty to the community and the environment.

Cattle, Wealth, and the Irish Diet – Livestock Under the Law

In early Irish society, cattle were the cornerstone of both economy and cuisine. They weren’t just a source of meat and milk—they were a currency, a status symbol, and a legal measuring stick. The Brehon Laws reflected this reality, offering intricate rules around the care, value, and use of livestock.

A man’s wealth was often measured in cattle, particularly cows, which were more valuable than gold in many respects. Fines were paid in cows; dowries included them; honour prices—essentially a person’s social worth—were set in bovine terms. And with that much at stake, the laws went to great lengths to protect animals and regulate their management.

If someone’s cow was stolen or injured, the law determined exact compensation based on the cow’s age, health, and productivity. If a bull broke into a neighbour’s field and caused damage, the owner was liable. There were even guidelines for fair milking, grazing rights, and how to share the offspring of a loaned animal.

From a dietary point of view, cattle provided much more than beef. Milk, butter, curds, and cheese formed a major part of the early Irish diet, especially among the rural population. The laws made distinctions between who was entitled to what kind of dairy produce, based on status and season.

Even pigs and sheep had their place in the legal code, with pigs often associated with feasting and hospitality, and sheep valued for both wool and meat. But cows remained king—legal tender with hooves.

Hospitality and Feasting – When Generosity Was the Law

In early Irish society, hospitality wasn’t a choice—it was a legal and moral obligation. The Brehon Laws placed a high value on feeding others, particularly guests, travellers, and those of lower status. Sharing food wasn’t just a gesture of goodwill; it was a matter of honour and legal duty.

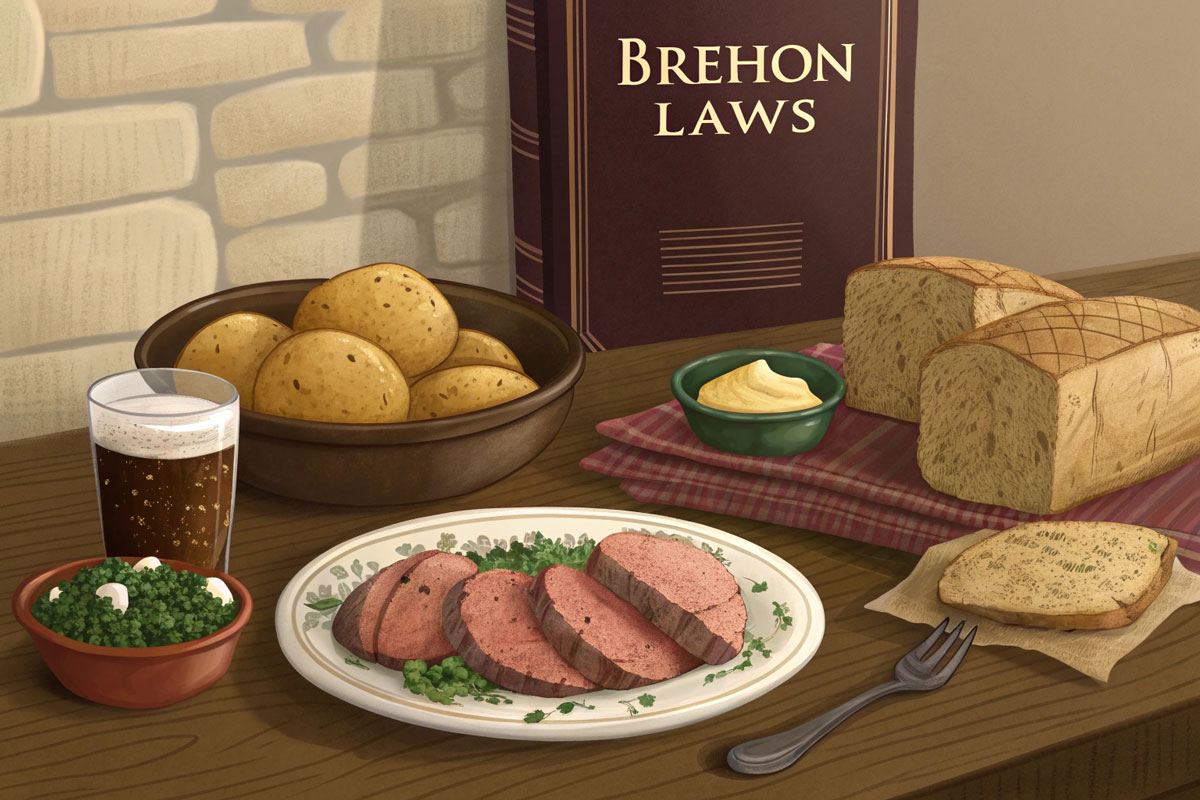

A chief or noble was expected to maintain an open house, known as a bruiden, where people could seek shelter and be fed. The laws even specified what kind of food should be served depending on the guest’s status—from bread, butter, and milk to pork, ale, and honey. Failure to provide appropriate hospitality could result in fines or damage to one’s social standing.

Feasting, too, was a regulated affair. Tribal gatherings, seasonal festivals, and ceremonial events often involved large communal meals, and the Brehon Laws ensured these were handled fairly. Seating arrangements, portions, and even the order of serving food were based on rank and honour price. An insult at the table could have legal consequences—particularly if someone was served out of turn or offered a lesser cut of meat.

Interestingly, bards, druids, and foster children were entitled to certain foods by law, often the best on offer, underscoring the belief that feeding people well was a sacred act as much as a social one.

In this ancient legal system, a shared meal was a binding force, weaving together honour, community, and culture—one loaf, bowl, or roast at a time.

Seasons, Sustainability, and the Legacy of the Brehon Laws

The ancient Irish lived in deep rhythm with the land and its seasons, and the Brehon Laws reflected this connection. Food production, preservation, and consumption followed seasonal cycles, not only for practical reasons but as a matter of law and social order.

The year was divided by agricultural festivals—Imbolc, Bealtaine, Lughnasa, and Samhain—which marked key points in the farming calendar. These times weren’t just for celebration; they were legal markers for grazing, harvesting, storing, and sharing food. For example, land couldn’t be overgrazed in winter, and certain crops were protected during growing seasons.

Food preservation was also built into the legal mindset. Whether it was salting meat, fermenting dairy, drying herbs, or storing grains, the goal was sustainability. Waste was not only impractical—it was frowned upon legally and culturally. The laws encouraged long-term stewardship of land and resources, holding farmers accountable not just for what they produced, but for how they maintained the health of their soil, herds, and harvests.

Though the Brehon Laws fell out of use centuries ago, their principles—respect for the land, responsibility in food production, fairness in distribution—still resonate today. In an age of climate challenges and industrial food systems, these ancient rules offer a surprisingly modern lesson: that food is not just fuel, but a social, environmental, and ethical bond.